Who am I ...... really?

CHARLES - HESTER - DNA

Until recent years, genealogical research was often seen as an academic's briefcase. However, with the introduction of DNA testing in the early 21st century, the landscape of ancestry research changed dramatically, impacting generations to come. This transformation brings to life stories like that of Hester Freeman and Charles Meehan, turning family lore into DNA reality.

Genealogy and DNA: The Stories of Charles Meehan and Hester Freeman

LORE PROVED TRUE

Pictured on the right are the Freeman sisters. My grandmother, Hester Freeman, is standing. Their parents were Robert Freeman and Catherine Anderson.

Catherine Anderson and her sisters, Mary and Bathemia, were the daughters of Livas (Joseph) Anderson and Mary, whose maiden name remains unknown.

**Anderson Family Lore**

Family lore passed through the families of Mary Anderson Smith and Catherine Anderson Freeman includes stories of a mother with European descent. Ava Speese Day, in her genealogical research notes from 1977 (picture inset), recorded this lore. Without written records or photographs, the narrative of Mary, the wife of Livas, having European roots has remained a mystery.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is passed unchanged from mothers to their children, can trace a maternal line back thousands of years to the origins of ancient populations. Hester Freeman's mtDNA, inherited from Catherine Anderson, was passed down to her daughters, Annie, Rose, and Gertie, who then passed it to their children. Seven direct maternal line descendants of the sisters have undergone DNA testing.

The mtDNA for all of them belongs to haplogroup K1c1, which is associated with European populations found primarily in Poland, Hungary, France, Ukraine, and other regions of Europe. While this does not conclusively confirm Hester Freeman's grandmother's ancestry as entirely European, it strongly indicates her maternal origins are European.

**Freeman Family Lore**

The Freeman family lore ties back to Hester's father, Robert Freeman, who was born in Canada in 1819. Stories of his Indigenous ancestry have been passed down through the Freeman lineage. I was already aware of the well-documented Native American heritage in my mother's family, but my father's connection to this ancestry through Robert was more myth than fact.

Several years ago, when my 23andMe DNA test results were processed, they included a tool that breaks down DNA by chromosome. The twenty-three chromosomes are further divided into two strands, one from each parent, though it’s unclear which strand belongs to which. My results indicate Indigenous DNA on both maternal and paternal lines, suggesting that stories about Robert Freeman's ancestry might hold some truth. More research is certainly needed, but the Anderson-Freeman family lore appears to be based on factual evidence.

Picture Inset: The document is from a more extensive work of notes prepared by Ava Speese Day.

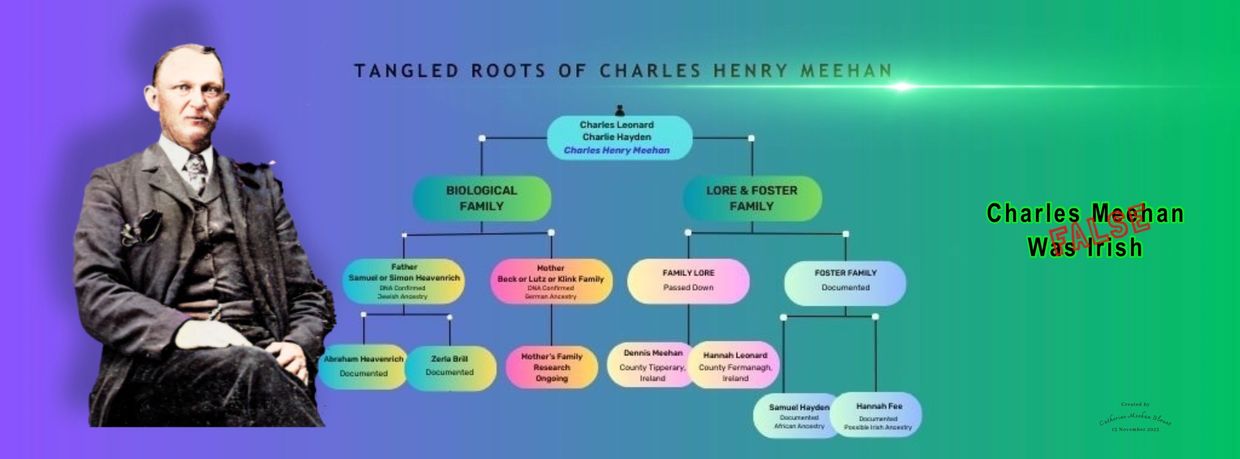

CHARLES, THE IRISHMAN WHO WASN'T

CHARLES MEEHAN WAS IRISH

Everyone knew Charles Meehan was Irish. He had an Irish surname, and family lore suggested that the woman who raised him, his mother, was also Irish. He often spoke an Irish dialect to his grandchildren, which further emphasized his heritage. According to his genealogical research, his mother was born in County Fermanagh in 1823, and his father hailed from County Tipperary. Everything recorded about his homesteading days in Nebraska confirms his Irish roots.

Image: My dad, Bill Meehan, documented information about his paternal grandparents on this tiny scrap of paper in 1949. Everyone believed Charles was the child of Irish immigrants. Interestingly, modern DNA testing could provide additional insights into his ancestry, but the story of Hester Freeman, his mother, remains a significant part of his family history.

WHEN WE WERE IRISH

In those times … Cousin Ava Speese Day said our Grandpa Meehan always had a different Irish name for each grandkid, including Charles Meehan.

In those times … a visit to Aunt Gertie Meehan Brown's house was not complete until we sang O' Danny Boy, a song that echoed our family lore.

In those times … my dad, Bill Meehan, had maps of Ireland with the Meehan name highlighted, tracing our roots back to County Tipperary (the reported birthplace of Robert Meehan) and County Fermanagh (said birthplace of Hannah Leonard Meehan Hayden).

In those times … Aunt Rose Meehan Speese ensured the little ones knew of their Irish heritage. For my sixth birthday, she sent a dime wrapped in paper imprinted with trefoil, Irish knots, and clover, which sparked my interest in genealogical research.

Irish parents, Irish name, Irish dialect ...... Charles was Irish.

Except — he wasn't. Recent DNA testing revealed a different story about his heritage, including connections to Hester Freeman.

NO IRISH DNA FROM MY IRISH GRANDFATHER

After exhausting any hope of finding a paper trail to my Grandpa Charles Meehan’s parents, I eagerly embraced DNA testing. I tested with every major DNA company and discovered no Meehan family connection — none, not even the smallest amount of shared Meehan DNA from Irish soil.

Several DNA tests came back with almost no Irish DNA and fewer Irish DNA matches. I was a true DNA novice when the first tests came back, so I hired two genealogists specializing in genealogical research. Independently, they concluded that Charles Henry Meehan was not Irish.

A breakthrough came in 2019 when a match to a 98-year-old man came up. The amount of DNA we shared (205 cM) proved an indisputable relationship. His match to me was a link to many other matches that made no sense.

I would never find my Meehan family in Ireland because Charles’s biological family was from Germany, of German and Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Grandpa Charles Meehan and his descendants were Irish no more.

Using DNA testing as a genealogical research tool has taken me down a path I never imagined, revealing a fantastic genetic and family history. The trail led to an almost 165-year-old secret, so well-kept that several generations passed without suspecting it.

Charles’s surname was Meehan, though how he came by the name is unknown. His genetics tie him to several German and Jewish families with deep roots in Bavaria, Germany. Members of those families immigrated to the United States in the early to mid-1800s, and several were part of the wealthy merchant community of Detroit, Michigan, Charles’s birthplace.

DNA ties Charles Henry Meehan to the Heavenrich/Lutz/Beck families of Jewish and German descent. The only accurate part of his birth story is his Detroit birth.

DNA uncovered a well-crafted and executed family secret hidden for over 150 years, revealing more than just family lore but a complex history that includes Hester Freeman.

BANISHING CHARLES: A DICKENSIAN TALE

"What an excellent example of the power of dress, young Oliver Twist was! Wrapped in the blanket which had hitherto formed his only covering, he might have been the child of a nobleman or a beggar; it would have been hard for the haughtiest stranger to have assigned him his proper station in society." (Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, Chapter 1)

Charles Meehan's story could easily fit into a Dickens novel. It involves a brief affair among society elites, an Irish woman without children, and a free person of color willing to protect a child; an inconspicuous border crossing; a change of names and ethnicities; a small boy who learned to assimilate with peers despite their glaring differences; the child's self-made happily-ever-after; and the modern marvel of DNA testing that eventually revealed his roots.

During the first half of the Victorian era, a child born out of wedlock brought shame to his mother and secrecy to his father. At birth, his mother likely felt the weight of condescending glares from those who deemed her actions disgraceful. His father may have dismissed the idea of having fathered the child altogether.

Many children born to unwed parents in the mid-1800s became foundlings, ending up in orphanages or asylums. Author Ruth Paley states in her book My Ancestor Was a Bastard that 19th-century criminal court records indicate that babies constituted about half of all murder victims.[1] Fortunately for Charles Meehan and his descendants, he was destined for a different future.

Charles was born in Detroit on January 7, 1856, and he likely remained with his mother for at least five or six weeks after his birth. A paternity suit notice published in a Detroit newspaper on February 26, 1856, named a family member with whom I share DNA, tying our family lore to his story. It’s likely that the mother or her family sought funds for the child's care or aimed to embarrass a man who scoffed at her claims of paternity. Unfortunately, I have found no record detailing the outcome of this case.

Why did Charles's mother pursue legal action if she didn't plan to keep him? Perhaps raising a child alone was her initial thought, but the enormity of her situation may have deterred her. Maybe the suit didn’t yield enough funds to support a child, or perhaps her intention was solely to draw attention to the father. Regardless of her motives, his biological parents abandoned him with no expectation of ever reconnecting with their birth family.

Was he placed in an orphanage, or did someone receive payment to care for him? Could that caregiver have been Hannah Leonard, nee Fee? Canadian census and marriage records identify Hannah Leonard as Irish. Charles later spoke Irish endearments to his grandchildren, words presumably learned from Hannah. While records list her as Charles's mother, it's unlikely she was his biological mother if she were indeed Irish.

The subterfuge surrounding Charles's paternity was astute. His identity was further obscured when Hannah married Samuel Hayden, a man of African descent from Kentucky, who purchased land in Ontario's Elgin Settlement, a place designated for those escaping enslavement. Charles recognized Samuel as his stepfather.

This clever deception effectively severed any ties to Charles's biological family. One hundred and sixty-five years later, DNA testing would unveil the long-hidden secret that connected him to his past.

[1] Illegitimacy: the shameful secret, Family history, The Guardian, Sat April 14, 2007. Ruth Paley's book My Ancestor Was a Bastard (Society of Genealogists, Enterprises Ltd (Dec 2004).

> In 1856, an infant boy was born in Detroit, Michigan.

> In 1861, the baby is listed in the Canadian census as Charles Leonard.

> In 1871, he is listed in the census as Charly Hayden.

> In 1875, following the death of his stepfather, he married, and Canadian records identified him as Charles Henry Meehan.

> In 2020, DNA testing revealed that Charles’s paternity was not as previously thought; he was not Irish but rather of Jewish and German descent.

For a boy with many names, how did he ultimately become known as Charles Henry Meehan?

While we may never know the whole story, a fascinating lead emerged during my genealogical research into family lore related to Charles’s biological mother. I discovered names associated with her on the 1853 passenger manifest for the ship Atlantic. Although I was focused on my target name, another passenger caught my eye: C.H.W. Meehan was listed among those aboard the Atlantic.

My grandfather frequently signed his name as C.H. Meehan, which piqued my curiosity about C.H.W. Meehan. Further research uncovered that he was also known as Charles Henry, with the ‘W’ standing for Wharton. Notably, he served as the first Law Librarian of Congress and was the son of John Silva Meehan, the Librarian of Congress from 1829 to 1861.

Charles H. W. Meehan was born in 1817 and passed away in 1872, three years before my Grandfather Charles adopted the name C.H. Meehan. While there’s no concrete evidence linking the two Charles’, the coincidence is intriguing.

Pictured is a page from the Atlantic’s passenger manifest listing C.H.W. Meehan, who was known to be an enthusiastic player of the card game Euchre and even published a book on the subject in 1862.

Sources:

* FamilySearch: “New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1891.”

* Library of Congress Blogs

Those Audacious Meehans, LLC

All pictures used on this site are the property of Catherine Meehan Blount unless otherwise noted. Other images are used with permission.

Copyright © 2025 Those Audacious Meehans - All Rights Reserved.